Approximately 60 miles (or around 100 kilometers) east of Rapid City, South Dakota is Badlands National Park, a rugged and sprawling area under the National Park Service. Continuing on my journey to get as much value as possible out of my America the Beautiful Annual Pass and visiting as many national parks as reasonable during my road trip, I decided to stop by Badlands.

I mentioned this in a previous blog post, but my stay in Rapid City hasn’t particularly been optimal due to the weather—it has been unmanageably windy (up to the point where a box containing a large pizza—which isn’t exactly the lightest thing ever—literally nearly took flight out of my hand, and would have if I didn’t notice and clamp down on it with my chin), and I also got snowed in for a few of the days… not to mention the overall extremely cold temperatures.

Because of this, I was unsure how many more opportunities I would have to get out and explore, so I decided to assume that I wouldn’t be able to return to Badlands, and planned to be able to see as much as I could in one day.

Like usual, I took a ton of photos. I tried to take pictures of informative signs along the way, but it’s very difficult to remember exactly where each photograph was taken because my Canon PowerShot G7 X Mark II doesn’t have built-in GPS, and I take a ton of stops.

With that being said, I took stops in this order, and the photos below are posted in chronological order: Hay Butte Overlook → Pinnacles Overlook → Ancient Hunters Overlook → Yellow Mounds Overlook → Conata Basin Overlook → Homestead Overlook → Burns Basin Overlook → Prairie Wind Overlook → Panorama Point → Bigfoot Pass Overlook → White River Valley Overlook → Fossil Exhibit Trail.

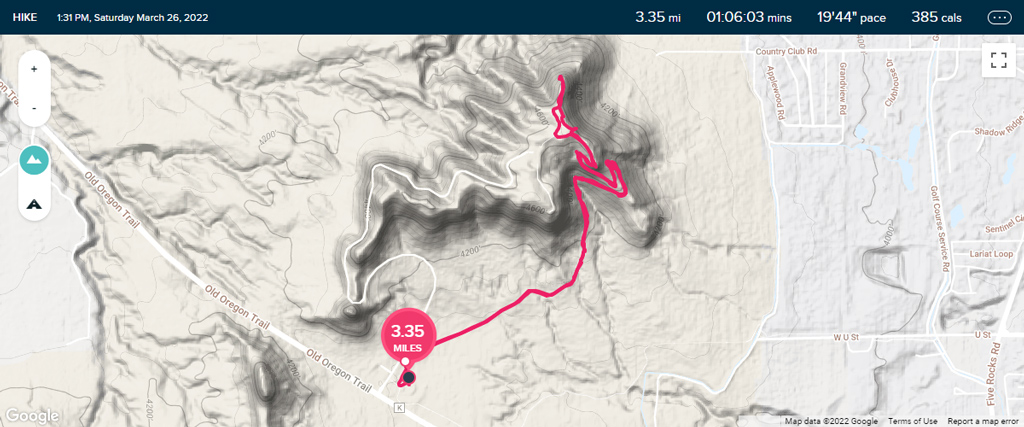

From there, I arrived at the Saddle Pass Trailhead. Because I had a plan to see as much as possible in a single day, I didn’t really do that many hikes—I would only take quick walks no longer than half a mile at each overlook and viewpoint—but I definitely wanted to hike Saddle Pass Trail because of how allegedly technical and challenging it was. With that in mind, I started climbing and realized that, yes, it was indeed extremely technical and challenging.

Then I arrived at a huge mountain. I had already scrambled up and scaled a bunch of rocks, and even crawled under some small openings in the rocks to get to where I was, and realized there was absolutely no way that it could get even more difficult—up to the point where you’re basically rock climbing now—and still be listed as a “trail.” My realization was correct—when I backtracked and looked around a bit, I discovered that I completely missed the real trail and went the very wrong direction. The real trail was much, much easier, and although it was relatively steep, it was completely manageable.

There was a very nice view from the top.

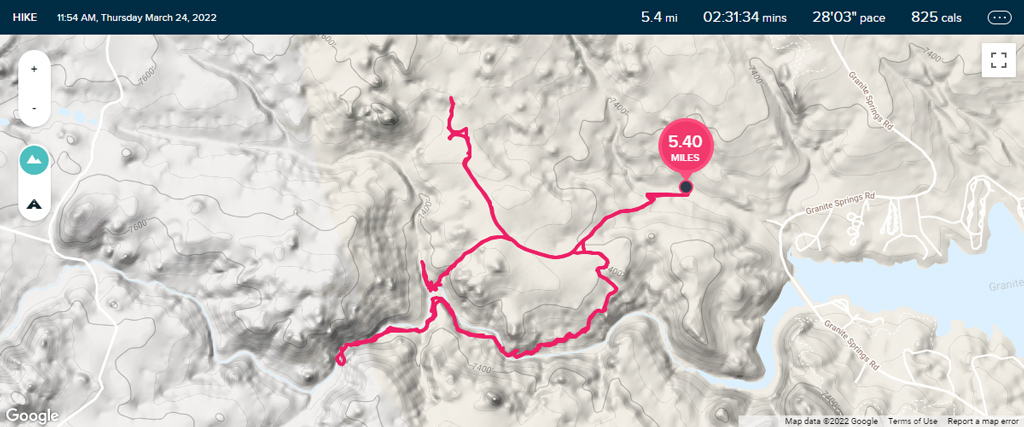

After Saddle Pass, I made a quick pass through Cliff Shelf Nature Trail, then arrived at my second “main” hike, Notch Trail. Although these trails that I’ve been hiking have been relatively short, I had completed a lot of them by that point, so the fatigue was very slowly building up. Still, Notch Trail was the one I was looking most forward to, as it was one of the top-rated trails on AllTrails for Badlands National Park.

If you look closely at the photograph below, you’ll see a wooden ladder in the middle leading up to the top of the hill. That was the most challenging part of the climb, and this trail is definitely not for people who are afraid of heights or have ankle or knee problems, especially considering that the ladder was a little wobbly at some areas, but if you’re comfortable with your maneuverability and climb confidently, it’s definitely doable. There was a bit of traffic backed up there as people tried to get up and down, but everyone I saw eventually made it.

I feel like Notch Trail would’ve been fairly leisurely for the remainder of the hike, but the high winds during the day I visited made it a bit more tricky. There are some areas along the middle of the trail that has some pretty steep bluffs, so I had to be careful not to be blown off balance and risk falling. I eventually made it to the summit, which had some amazing views.

For some reason, I don’t really have too many great photos from the top that I find satisfying (either that, or there isn’t really much in the pictures to provide visual scale to see just how high up it was taken), but I think a big “wow” aspect of the hike here is the contrast between the climb and the summit. Throughout the hike, you’re generally surrounded by a lot of rock and have fairly limited forward visibility due to the path winding between rock formations. However, once you reach the top, you suddenly have an explosively wide, vast view of Badlands National Park facing south.

After Notch Trail, I also walked the Window Trail, named as such because the end of the trail has a rock formation that looks like a window. … This photograph below clearly is not that window, but it was on my SD card chronologically during the time that I would’ve been at Window Trail, and it was unique scenery relative to the rest of Badlands, so I decided to share it.

My final hike of the day was Door Trail. From the parking lot, it leads down to an area where you can read about the Badlands’ badness via some informational signs, and then take some stairs to walk out directly into the badlands. The trail takes you about half a mile out, and is named “door” because it is supposed to be a door to the real badlands—the trailless backcountry badlands of over 300 square miles (or approximately 800 square kilometers) surrounded by the Badlands Loop State Scenic Byway, Interstate 90, South Dakota Highway 44, and South Dakota Highway 73.

For my final stop before reconnecting onto Interstate 90 and heading back to Rapid City, I took a stop at the Big Badlands Overlook, the location where a lot of the most signature photos of Badlands National Park are taken.

Badlands was very different than the other recent national parks I’ve visited—Grand Canyon, Zion, Canyonlands, Arches, and Wind Cave. Although Badlands might not have been as impressive or breathtaking as some of the bigger national parks, Badlands still had its own special charm to it—the charm of something being so rugged, yet still having its own unique kind of beauty.

I don’t have a map with GPS tracking because my walks and hikes were split up across many smaller trails, but according to my fitness tracker, my total distance was right around 9 miles. That ended up being very similar to my hike at the Grand Canyon this past December, but it was a lot less tiring because this was nine miles split up over several hours with many driving breaks in between.

If you choose to make your own trip to Badlands National Park, I think a two-day trip is the minimum you’ll need to see everything there is to see, and still do enough activities to make it feel like you’ve experienced the true Badlands experience. I only took stops along South Dakota Highway 240, but there are many other paths you can take to see other areas of Badlands.